Problématiques et blessures en yoga.

Comprendre et prévenir les blessures de yoga

Loren M. Fishman, MD, 1 Ellen Saltonstall, RYT, 2

Susan Genis, RYT, Esq.2

1.Columbia Collège des médecins et chirurgiens 2. New York, New York

JOURNAL INTERNATIONAL DE THÉRAPIE DU YOGA - N ° 19 (2009) / extrait

Résumé :

Pour obtenir une estimation initiale de la nature et des causes des blessures liées au yoga (à la pratique de hatha-yoga / A.P.), nous avons invité 33 000 professeurs de yoga, thérapeutes du yoga et autres cliniciens à participer à un sondage de 22 questions. Le sondage a été mené en collaboration avec l'Association internationale des yoga-thérapeutes (IAYT), Yoga Alliance et Yoga Spirit.

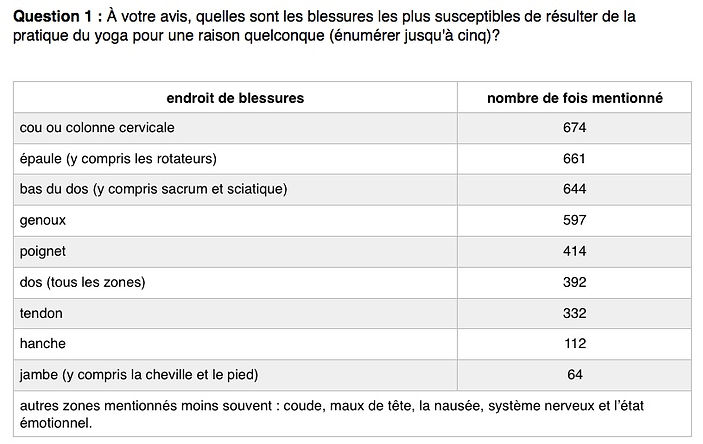

Entre mai et octobre 2007, 1 336 réponses provenaient de 34 pays. Une majorité de participants croyaient que les blessures les plus courantes et les plus graves se produisaient dans le cou, le bas du dos, les épaules et les poignets et le genou. Une mauvaise technique ou un mauvais alignement, une blessure antérieure, un effort excessif et une instruction inadéquate étaient les causes les plus souvent citées de blessures liées au yoga.

Par exemple, les blessures au cou ont été attribuées à Sirsasana (posture sur la tête) et sarvangasana (chandelle); les blessures au bas du dos étaient associées à des torsions et à des courbures vers l'avant; les blessures à l'épaule et au poignet étaient liées à adho mukha svanasana (chien vers le bas) et à des variations de pose de planche (par exemple, chaturanga dandasana, vasisthasana); et le genou était le plus fréquemment blessé dans virabhadrasana (pose de guerrier) I et II, virasana (pose de héros,) eka pada rajakapotasana (pose de pigeon à une jambe) et padmasana (pose de lotus).

Introduction

La plupart des autorités semblent être d'accord avec l'American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons que «les récompenses du yoga emportent sur les risques physiques potentiels, tant que vous prenez des précautions et faites les exercices avec modération, selon votre niveau de flexibilité individuel». L’augmentation des blessures a été notée parallèlement à la popularité croissante du yoga, et une variété de facteurs sont généralement, mais non empiriquement, énumérés comme les causes.

Si le yoga doit être accueilli dans le répertoire de guérison de la médecine, puis en plus de démontrer ses avantages, il incombe à la communauté du yoga d'estimer ses responsabilités et de déterminer, dans la mesure du possible, comment «ne pas nuire» à sa santé.

Comprendre les causes et la fréquence des blessures liées au yoga est important pour plusieurs raisons: 1) cela permettra aux communautés de Yoga et de santé d'évaluer de manière responsable les avantages et les risques du yoga. 2) aidera à protéger les pratiquants et à prévenir les blessures. Cela permettra donc à l'ensemble de la communauté des soins de santé d'accepter le yoga de manière intelligente et éclairée.

Le Yoga Journal a publié un excellent article sur ce sujet en juin 2003, intitulé «Perspicacité des blessures … » L’auteure Carol Krucoff souligne tout de suite la question de l'attitude en disant qu'elle a« appris à ses dépens que le yoga n'est pas une évidence. » Krucoff cite de nombreux enseignants et experts dans le domaine, qui notent que les blessures en yoga sont le plus souvent causées par l’excès de zèle et des attentes irréalistes chez les étudiants, une formation inadéquate de enseignants, technique médiocre et classes nombreuses. Krucoff note que l'aspect du yoga axé sur le marché a «engendré une ruée vers les instructeurs, entraînant l'embauche de certains enseignants ayant reçu une formation inadéquate».

L'article de Pamela Paul «When Yoga Hurts», paru dans le magazine Time en octobre 2007 fait écho à ces problèmes. Paul soutient que l'augmentation de la fréquentation des cours de yoga entraînera logiquement une augmentation du nombre total de blessures liées au yoga. Paul mentionne également que les nouveaux étudiants en yoga peuvent ne pas être en forme et s'attendre à ce que le yoga soit facile, entraînant des blessures dues à des efforts excessifs. Ici, l'expérience et les conseils de l'enseignant sont cruciaux. Paul souligne le manque de formation adéquate des enseignants comme un facteur dans l'augmentation des blessures.

L'article de Time cite 13 000 blessures de yoga documentées sur une période de trois ans. Avec environ 14 millions de personnes pratiquant le yoga, ce n'est qu'une blessure sur mille praticants. Si cette statistique est exacte, cela rend le yoga plus sûr que de nombreux autres types d'exercices. Cependant, ce chiffre a été rapporté par la communauté médicale (salles d'urgence et médecins), pas par la communauté du yoga. Par conséquent, il n'est pas clair si la figure reflète pleinement l'expérience des pratiquants de yoga qui ne peuvent pas chercher des soins médicaux pour soigner les blessures liées au yoga.

La tentative d'enquêter sur les blessures de Yoga est rendue difficile par de nombreux facteurs:

-

l'absence de tout protocole de rapport formel au sein de la communauté du yoga

-

le large éventail de blessures

-

et le défi d'identifier les causes spécifiques de toute blessure.

Pourtant, il y a peu de doute que de telles blessures se produisent.

Le sondage

Pour lancer le processus d'auto-examen, nous avons créé un questionnaire en ligne anonyme de 22 questions à choix multiple. Nous avons conçu le sondage sur une période de quatre mois, obtenant les opinions et les conseils de nombreux enseignants et thérapeutes de yoga de la communauté internationale, ainsi que des conseils de conception de la part de statisticiens et de chercheurs.

Avec la coopération de trois organisations internationales (IAYT, Yoga Alliance et Yoga Spirit) et diverses autres sources d'adresses e-mail de professeurs de yoga et de thérapeutes, nous avons envoyé l'URL d'un sondage en ligne à plus de 33 000 professeurs et thérapeutes de yoga.

Nous avons demandé aux répondants de partager leurs opinions en fonction de leur expérience réelle (et non de ce qu'ils avaient lu ou entendu) avec leurs élèves, leurs clients et eux-mêmes. On a demandé aux répondants de signaler les blessures seulement s'ils étaient raisonnablement certains que la pratique du yoga les a provoqués, qu'ils soient survenus lors de leurs séances, à la maison ou en présence d'un autre pratiquant. L'ordre des choix de réponses aux questions à choix multiples a été randomisé dans chaque présentation individuelle, afin de minimiser le biais de réponse. Les répondants n'étaient nullement rémunérés pour la participation

Répondants

Il y a eu 1 336 réponses à l'enquête, soit un taux de réponse de 4%, sur un total de 34 pays. La majorité des réponses provenaient des États-Unis (81,4%), du Canada (11,7%), de l'Australie (1,3%) et du Royaume-Uni (1%).

Le statut professionnel non exclusif des répondeurs était: professeur de yoga (91%),

massage-thérapeute (8%), entraîneur personnel (7%), médecin (2%) et autres (41%).

Le nombre d'années pendant lesquelles les répondants ont enseigné le yoga / l'utiliser dans leur pratique correspond à une courbe de distribution normale raisonnablement bien centrée à 5-10 ans: 0-2 (9%), 2-5 (20%), 5-10 ( 27%), 10-20 (20%), 20-30 (11%),> 30 (7%) et autres (6%).

La catégorie «autre» comprenait à la fois des enseignants en formation et des enseignants et thérapeutes à la retraite. La plupart des répondants ont vu soit 11-30 (35%) ou 31-75 (35%) clients / patients par semaine. Environ 18% ont vu 1 à 10 clients, 10% en ont vu 75 à 150 et 2% en ont vu plus de 151.

Les répondants ont énuméré une variété de styles ou de traditions de yoga, comme suit:

-

Hatha (16%)

-

Vinyasa (10%)

-

Iyengar (7%)

-

Anusara (6%)

-

Ashtanga (5%)

-

Kripalu (5%)

Les auteurs croient que la désignation «Hatha» désigne généralement les enseignants et les thérapeutes qui se considèrent éclectiques, n'ayant aucun lien ferme et / ou exclusif avec une école de yoga en particulier.

Y a t-il plus de blessures de yoga aujourd'hui qu'auparavant?

-

39% des répondants ont répondu oui

-

36% ont répondu non

-

et 25% ont répondu ne pas le savoir.

Pourquoi y a-t-il plus de blessures maintenant que par le passé? Seuls ceux qui ont répondu «oui» ci-dessus ont reçu cette question. Les répondants pouvaient choisir plusieurs raisons, et les pourcentages suivants de participants approuvaient chaque raison:

-

Effort étudiant excessif 81,4%

-

Formation inadéquate des enseignants 68,2%

-

Plus de personnes font du yoga en général 65.4%

-

Conditions préexistantes inconnues 59.5%

-

Grandes classes 47.0%

Prévenir les blessures dans le yoga lorsque des blessures ou des conditions préalables existent :

En ce qui concerne les blessures ou les conditions antérieures en tant que cause de nouvelles blessures, les enseignants et les studios doivent demander, et les étudiants doivent informer leurs enseignants, de toutes les conditions préexistantes. Néanmoins, ces conditions peuvent ne pas être divulguées. Par conséquent, les enseignants devraient être proactifs en mentionnant les contre-indications d'une pose. Les enseignants doivent avoir la connaissance requise du corps pour savoir comment ajuster la pratique d'un élève afin d'éviter les risques liés aux conditions préalables. Dans chaque section ci-dessous, nous avons noté quand un soin particulier est recommandé.

Prévenir les blessures au cou

Le rachis cervical est la partie la plus vulnérable de la colonne vertébrale car c'est la plus mobile. Les deux types de poses dans lesquels le plus grand soin est nécessaire pour protéger le cou sont les back-bends et les inversions.

En backbending, la compression vertébrale et le conflit nerveux se produit quand un étudiant de yoga est trop agressif, en poussant la tête et le cou en bhujangasana (posture de cobra), urdhva mukha svanasana (chien vers le haut), ou ustrasana (pose de chameau). Ceci est particulièrement vrai dans des poses telles que l'ustrasana où la gravité jouera un rôle dans la prise de la tête en arrière. L'instruction clé (et la sensibilisation) qui protégera le cou est de cambrer la tête en arrière seulement après avoir atteint l'arcade maximale possible dans la colonne thoracique. Il est également utile de maintenir un tonus musculaire à l'avant du cou. Avec ces actions protectrices, le mouvement de cambrure est réparti uniformément à travers la colonne vertébrale.

Prévenir les blessures au bas du dos

inclinaisons vers l’avant :

Les considérations de l'anatomie de la colonne vertébrale, du bassin et des jambes sont pertinentes ici. Le risque dans la plupart des virages en avant, tels que uttanasana (inclinaison debout vers l'avant) ou pascimottanasana (inclinaison assis vers l’avant), est que l'étroitesse des ischio-jambiers empêchera le bassin de basculer, provoquant une flexion excessive du rachis lombaire plutôt qu'une flexion des hanches. Cette flexion lombaire excessive pourrait entraîner des entorses des ligaments ou des muscles spinaux, tels que la musculature dorsale et lombaire et le quadratus lumborum, et pourrait également causer une hernie discale, ou une fracture du coin ostéoporotique. Ici, une blessure antérieure, un effort excessif, une instruction inadéquate et une mauvaise technique sont une combinaison déloyale.

Prévenir les blessures au bas du dos en torsades

Une flexion excessive de la colonne vertébrale lombaire est également un risque dans les rebondissements assis, tels que ardha matsyendrasana (moitié poisson), et la flexion combinée à la rotation exerce une force particulière sur les disques vertébraux. Assis avec les hanches sur une couverture pliée peut aider le bassin à incliner vers l'avant, en maintenant l'arche naturelle et la longueur de la colonne vertébrale lombaire, même si une jambe se replie vers la poitrine. Les accessoires tels que les blocs ou les oreillers peuvent être utilisés pour éviter les blessures dues à un effort excessif dans les torsions inclinables et pour soutenir l'élève lorsque les épaules, les bras ou les jambes ne peuvent pas reposer facilement sur le sol.

Prévenir les blessures lombaires dans les back-bends

Dans les back-bends tels que ustrasana (pose de chameau) ou ûrdhva mukha svanasana (pose de chien tournée vers le haut), des lésions de la région lombaire se produisent souvent parce que la colonne thoracique ne se plie pas, forçant le rachis lombaire à se sur-extensionner. Ici, un élève trop zélé peut contracter le bas du dos, en prenant la forme extérieure de la pose sans tenir compte de la technique ou de la conscience. Dans de nombreux cas, c'est à l'enseignant de sensibiliser les élèves.

Prévenir les blessures aux épaules et poignets

Adho mukha svanasana (pose de chien orientée vers le bas), chaturanga dandasana (pose à quatre membres), et vasisthasana (pose de planche latérales), toutes poses qui nécessitent de porter du poids sur les bras et les mains, les épaules et les poignets. Beaucoup d'étudiants essaieront avec diligence de réaliser la pose complète même sans les instructions techniques ou la force requise pour le faire en toute sécurité. Encore une fois, l'œil vigilant d'un enseignant attentif à un effort excessif et à un mauvais alignement peut faire la différence entre l'apprentissage et les blessures. Quand il y a une différence de capacités entre les élèves dans une classe, l'enseignant doit accommoder et ne pas ignorer ceux qui ne peuvent pas encore pratiquer ces poses en toute sécurité, et fournir des alternatives dans des séquences fluides comme surya namaskar (salutation au soleil).

Prévenir les blessures aux genoux dans les Poses debout

Le genou est situé entre les os longs de la jambe supérieure et inférieure, et partage les muscles avec les articulations de la hanche et les articulations de la cheville. Cela rend le genou dépendant de l'alignement et de la mobilité des hanches et des chevilles pour sa sécurité. Des poses debout aux jambes larges comme la série virabhadrasana (pose de guerrier) imposent une telle exigence d'étirement des muscles de la hanche que la sécurité des genoux peut être compromise.

Un repère de sécurité de base pour les élèves consiste à aligner le centre du genou avec le centre du pied, si le genou est sur le côté, devant ou à l'arrière du talon.